Gated communities, ghettos, and gentrification represent a perversion of the diverse spectrum of housing options that city advocates call for today. Ta-Nehisi Coates in his startling, yet brilliant, expose’ in The Atlantic “The Case for Reparations,” raises the bar on the discussion of “fair housing” with regards to African Americans who have been denied the opportunity for inclusion in the postwar rise of the middle class, pointing to past lending and real estate practices such as loans through the GI Bill, which would have provided home ownership to many African Americans returning from service in World War II, and red-lining. The resulting lack of diversity in many cities raises the question of what benefits can be enjoyed when Diversity is celebrated and encouraged.

In our research of metrics related to quality of life, leading to our creation of IfYouWereMayor.com in 2014, Diversity has consistently been a key factor in a city’s “livability index.” It is not easy to define, but relates to how well a community fosters social interactions, or “capital,” to reach its maximum potential. The sociologist Zachary Neal published a study last year that speaks to the balance needed between “bonding” social capital – the type found in tight-knit communities – and “bridging” social capital, where different communities and individuals interact and establish relationships to the benefit of the whole. Richard Florida has argued (here) that the lack of diversity in tight-knit groups can stymie innovation and that only by virtue of the interaction between groups can cities form the basis for innovation and prosperity. However, Neal’s research illustrates a more nuanced and mutualistic relationship between these two types of social interactions, and establishes the basis that: “The ideal community is big and diverse, but feels small and familiar.”

And there are real dividends when diversity is allowed to flourish. As early as 1782, the United States was referred to as a country where the people are “melted” into one harmonious culture – the great melting pot. More recently, this metaphor of assimilation has evolved to one of cultural pluralism or multiculturalism – a vast mosaic or kaleidiscope. From the onset of its founding, this diversity has always been considered one of our country’s greatest strengths.

In a recent article in the New York Times, researchers Sheen Levine of the University of Texas and David Stark of Columbia University point to their research on the presence of minorities in university settings, supporting the notion that “diversity improves the way people think.” The article continues, “By disrupting conformity, racial and ethnic diversity prompts people to scrutinize facts, think more deeply and develop their own opinions…. Diversity benefits everyone, minorities and majority alike.” It is not hard to imagine that our schools and universities are microcosms of our cities, and by extension, it is diversity that can establish empathy and trust among different types of people, whether it is based on race or resources, to make better decisions and choices that can benefit everyone.

Beyond these social benefits, diversity also presents economic benefits. Richard Florida’s gambit on the correlation between diversity and prosperity is borne out in a study by economists for the Bureau of Economic Research, entitled “Cultural Diversity, Geographical Isolation, and the Origin of the Wealth of Nations.” Florida shares the basics of this study (here), tracing the shift of communities from the relative isolation of agricultural economies that benefit from homogeneity, to more industrialized societies where geographical openness, cultural diversity, and tolerance lead to greater success. “Proximity, openness, and diversity operate alongside technological innovation and human capital as the key engines of economic prosperity.”

Preserving diversity can be a challenge. The conundrum, of course, is the tendency of prosperity to result in gentrification, a factor that can undermine the very diversity that has enabled a community to thrive. Neighborhoods that have affordable and/or attractive housing options in proximity to vibrant urban centers are seen as the best options for newly minted individuals and families. And, unfortunately, it is often minorities or the under-represented who are pushed out.

The results can be unsettling as evidenced in the recent Guardian headline (here): “San Francisco Tech Worker: ‘I don’t want to see homeless riff-raff’.” The World Resources Institute notes (here) that cities and their citizens must learn to manage affordability and diversity to make, and keep, their cities livable. This is not an easy task and cities must be pro-active by establishing creative affordable housing options and local business opportunities. Inviting possibilities such as live/work spaces for artists, density bonuses in exchange for more affordable rental units, or business districts that foster local entrepreneurship are tools that cities have utilized to great success throughout the US.

But, residents who can feel threatened by change often create insurmountable pushback, widely known as NIMBYism –“Not In My BackYard.” It’s visible in Mt. Pleasant where residents have rejected planning initiatives that could foster affordable housing through more dense development; in the bad blood that surrounds the redevelopment of the Sergeant Jasper; and, to a lesser degree, in the outright suspicion of the “gathering place” concept on James Island.

More success can be found if local residents are allowed to evolve their opinions along with the concepts initiated by developers or civic leaders. Lowcountry Local First went straight to the Cannonborough/Elliottborough neighborhood to float the idea of a pilot project to foster local independent businesses (here). The success of West Ashley’s Avondale neighborhood began as a grassroots initiative to create a lively, identifiable district as a viable and affordable counterpoint to downtown Charleston. The residents and merchants want to build on that success with support for the arts and culture and are hopeful that there are moves afoot for just such a plan. Avondale residents’ wisecracking swagger as the city works to foster the same kind of potential at the intersection of Dupont and Wappoo – Du-Wap – is worth following on Facebook.

Appreciating the payoff in diversity is paramount to a successful city but it requires that everyone participate in the process. With that scenario, a win-win can be on the books.

Life in cities and urban areas is characterized by a certain balance between private space and shared spaces, like parks, streets, shops, restaurants, and other public places. Most people who choose to live in the city can accept certain tradeoffs in their private realm (for instance, a somewhat smaller home or glimpses by the passerby to life through windows or gates). The appeal is the liveliness and amenities that anchor the sense of community.

One routinely hears the possibilities of “downsizing,” and there certainly appear to be trends in that direction (just consider the NYTimes bestseller The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo). Initially, it may be that children grow up, leave home, and parents find that the suburban house echoes disconcertingly. So the furniture is parceled out to those offspring apartments along with anything else that merits a new home. Closets are cleared and unfinished projects purged. Favorite toys might be boxed for safekeeping, but most of what remains is tossed off. That condominium in a much warmer climate holds so much promise of the mythological life of leisure. But, even in the case of the aforementioned purge, there are still vestiges of the “old” lifestyle that seem to cling, whether it is the hyper-applianced kitchen or master bedroom cum sitting room.

But the history of the US demonstrates nothing short of outright ambivalence to the idea of downsizing (noting that the aforementioned book refers to a Japanese art). Opportunity brought many early settlers to these shores. And, a rather damnable tendency to civilize the wilderness, convert the heathen, and exploit our natural resources has consistently propelled belief in our Manifest Destiny, to expand on every available morsel of the continent, letting no one (especially those who might have lived here for hundreds of years) stand in the way.

In the 18th century, it was the lure of the frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains, where trading and agricultural outposts were established beyond the original colonies. The 19th century offered up a duet of enthusiastic land-grabbing with the west coast. First, it was the discovery of gold that beckoned with the lure of riches. Then, the Homestead Act opened the great plains and prairie lands up to widespread settlement and cultivation in the aftermath of the Civil War. By the turn of the 20th century, audacious development fueled wild land speculation in otherwise off-the-beaten-track-places, like Florida. And by the time that real estate bubble burst, the Great Depression throttled the country with downsizing whether it liked it or not.

The consequences of expansion in the 20th century may not have the human cost that marked our country’s earlier 200 years – given the fates of Native and African Americans – but the post-World War II period certainly created a rather blighted and downright ugly landscape. Cookie cutter houses in sprawling suburban developments spun out around old, forsaken downtowns, hailing the newly minted windfalls courtesy of Uncle Sam’s GI Bill (the modern version of the Homestead Act).

Unfortunately, many urban areas today are the skeletal remains of former lives, following periods of depopulation more or less driven by fear, whether as the target of nuclear destruction, unhealthy living conditions, or bastion of crime. Individual cars slowly displaced trains and buses, and the interstate highway system became the hallmark of progress. By the late 20th century, the greener pastures of remote suburbia were dotted with souped-up homesteads [sic] cheekily referred to as “McMansions.” A hodge-podge of strip malls, gas stations, fast food joints, and auto dealerships often lay between downtown and residential areas creating a barrier to mending the rift that may never be overcome in some places.

But, the pendulum does swing. And, the frontier has shifted right back to where things were years ago – many downtowns and city centers once again hold appeal in a turnaround that could not be foreseen even fifty years ago. The sameness of the suburbs just doesn’t hold sway like it once did, and the interest in unique places with distinctive character and liveliness has created its own kind of gold rush of speculation and fortune seeking. Cities are absorbing loads of migrants with their burdens of suburban tendancies that don’t really fit neatly into the compact demands of the urban metropolis. Downsizing is really called for, and a treatise of hints in that realm might start with the following:

Give up the two-car lifestyle. At its most recent meeting, City Council members were struggling to consider whether downtown Charleston residents might be happy with only a single car. “We are a car culture,” Daniel Island’s baffled member noted. “Remember the Boulevard in Mt. Pleasant,” was another call from a councilman, futilely trying to make a relevant point. Given that many people discover (or at least eventually figure out) that it is faster and more practical to walk or bicycle to most downtown locales, it’s a little curious why there is even an argument in this beautiful, compact, and historic downtown. Granted, public transportation is wholly inadequate at this stage, but there are some enterprising efforts to fill the gap, such as a “free” car service called SCOOP, and an intermittent water taxi that really is an opportunity.

Small is the new black. Some people actually prefer the idea of living small in the first place – no annoying routines of upkeep nor are there worries about fostering a tendency to accumulate unnecessary “stuff.” And there are others who want to stay light, nimble and ready to move on as an essential part of youth and the esprit d’aventure. Some places have embraced this notion, providing groups of tiny houses and accompanying services for homeless people and families. A dissertation from a graduate student at MIT, and articles from The Atlantic, Huffington Post, and Charleston City Paper, offer some hints at the possibilities for tiny houses to provide shelter, and what may be on the horizon for homeless families in Charleston.

Perhaps downsizing, in this sense, is really more a sign of the advent of maturity. If we consider that the sameness of chain stores and franchise restaurants was symptomatic of our adolescence – a time when we wanted to be more alike – then, this stage actually underscores how our differences are what creates value, appeal, and real community. It just may be possible that we have the opportunity now to leverage our “downsized” resources to benefit everyone, by focusing on the important, and unique, characteristics in a city like Charleston that can make it more livable and accessible and beautiful.

And, then, who would want to leave?

That was the line printed at the bottom of the 1964 version of South Carolina’s Application for Registration to vote. The irony, of course, was that embedded within the application were tests or qualifications that particularly targeted the African American population and the poor for exclusion in the voting process. Here are two of the five “tests” of eligibility:

•I am not an idiot, or insane, a pauper supported at public expense or confined in any public prison.

•I will demonstrate to the Registration Board that: (a) I can both read and write a section of the Constitution of South Carolina; or (b) I own and have paid all taxes due last year on property in this State assessed at $300.00 or more.”

Or perhaps, you would prefer these questions from Georgia’s application for registration:

•Who is the Solicitor General of your State Judicial Circuit and who is the presiding judge?

•What does the Constitution of the United States provide regarding the suspension of the privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus?

•In what Federal Court District do you live?

•What are the names of the Federal District Judges of the state?

Now how about these examples of thirty questions on one of Louisiana’s literacy tests:

•Spell backwards, forwards.

•Print the word vote upside down, but in the correct order.

•Write right from the left to the right as you see it spelled here.

•Write every other word in this first line and print every third word in the same line, (original type smaller and first line ended at comma) but capitalize the fifth word that you write.

These examples and others may be found on the website of the Civil Rights Movement Veterans.

Some consider the elimination of these types of tests by virtue of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 merely a historical matter (Shelby County v. Holder). Others consider disenfranchisement of classes of voters to continue as a relevant question (see The Atlantic’s “What Does the Voting Rights Act Mean Today? or The NYTimes Magazine’s “A Dream Undone”). Racial issues remain a central theme in the political world of today – whether it is the gerrymandering the boundaries of a voting district, disqualifying US citizenship to naturalized children born in this country to immigrant parents, or requiring photo identification to cast a ballot.

Nine little Suffergets,

Finding boys to hate,

One kisses Willie Jones,

And then there are Eight.

The women’s suffrage movement has its own interesting history of opposition to the idea of women gaining the vote (see Mental Floss “The War on Suffrage“). The position of the privileged in both cases – race and gender – to deny the vote was often grounded in concerns with “societal disruptions.” The question of whether society would be better if blacks or women (or Hispanics or Asians) could vote, or whether it leads to a breakdown in peace and civility unfortunately remains a concern for some.

The recently released British movie, Suffragette, covers the UK’s movement (1918) and ends as the movement begins its inevitable shift to the United States (1920). The movie reveals the movement as bearing only a passing resemblance to the one embraced by mother and suffragette Winifred Banks of Mary Poppins fame. National Public Radio recently featured a story on the opposition to women’s suffrage in America (here). According to the political science professor Corrine McConnaughy, women who generally opposed the woman suffrage movement were women who were “doing, comparatively, quite well under the existing system, with incentives to hang onto a system that privileged them…Anti-suffrage leaders…were generally urban, often the daughters and-or wives of well-to-do men of business, banking or politics. They were also quite likely to be involved in philanthropic or ‘reform’ work that hewed to traditional gender norms.” This dichotomy can remain a difficulty for women who choose to work and even for those who seek political office. Attire, mannerisms, and “neglectful” child-rearing are often highlighted among peers, rather than qualifications, opinion, or expertise.

The overarching theme facing us at this point with voting is the question as to whether it is a “right” or a “privilege.” Given that “the right to vote” appears most often in the text of the U.S. Constitution – more than “freedom of speech,” “free exercise” of religion,” or the “right to keep and bear arms” – it would stand to reason that this point would not be an issue in the United States. But as we’ve seen already in the issue, for instance, surrounding the blacks’ right to vote, the exercise of voting is too often seen as something “granted by the powerful to the deserving.”

And, by extension, that privilege can be withheld if it is determined that YOU are less than deserving. Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, noted that Americans have been torn between “voting as a right and voting as something that only the right people should do,” even as we have ensured in our oversight of constitutional re-writes in Iraq or Germany that everyone is enfranchised regardless of race or gender (see The Atlantic “Voting: Right or Privilege?”).

If we truly believe that voting is a “right” provided without question by the United States Constitution, then it is critical that we exercise that freedom to protect our democracy, to proclaim our dissent, and to demand a seat at the table of decision makers. An elected official represents everyone, not just those who voted them into office (or paid for them to get there).

With elections still in full swing this season – runoff elections are scheduled in Charleston for instance for November 17, 2015 – prepare to parse the truth from an onslaught of a slightly different variety as the remaining candidates:

•Try to attract voters who cast ballots for other candidates

•Try to cast opponents in questionable light, and

•Get the message out to the people who voted for them in the general election on November 3rd to remember and show up again to vote

So don’t let your vote slip away. Your voice is needed, your ideas are critical, and your participation can galvanize the unified and inclusive image Charleston has projected to the world.

Don’t let this historical moment become an illusion. VOTE on November 17.

An educated workforce is one key element to individual and community economic success, and quality education enhances the livability of cities for all its citizens. Many cities that have developed and maintained economic strength in recent years have elevated the conversation regarding education and research outcomes. In Charleston, the civic government and larger community stands apart from the governance of the school systems, but everyone has a very real stake in student success.

The recent forums and debates in Charleston have underscored the issue of improving educational opportunities as critical to the future of the city and region. When the Charleston Digital Corridor hosted a forum for the mayoral candidates earlier in September, among the issues raised to the candidates, was the ongoing need for workforce development to meet the growing demands in the technology sector. The rise of the technology sector and the addition of Boeing and Volvo to the region’s manufacturing sector have increased the community’s expectations from both the secondary and post-secondary educational institutions.

The post-secondary response has been swift with area leaders and academics sensing the opportunities. The College of Charleston has added the I-CAT (International Cross-Curricular Accelerator for Technology) to weave business, computer science, and liberal arts skills together. Trident Technical College (here) has beefed up its offerings to include more skills needed in engineering and technology, and vendors like The Iron Yard (here) are also bringing focused technology training to the region. The Medical University’s research has expanded its focus deeper into biotechnology and bioengineering with such collaborative partnerships as Clemson University (here). Response within the public elementary and secondary school system has been relatively uneven, with larger schools introducing focused programs in most or all of the STEM subject areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Other schools have partnered with area businesses to incorporate some smaller programs with technology, entrepreneurship, or other specific skill training components.

Systemic inequity can plague a region, especially in the public pre-school, elementary, and secondary school education system. Wealthier areas tend to have better representation on the school board, better teachers and administrators, and more parental involvement. Other schools are vexed with issues that stem from inconsistency in teacher quality, programs, or administration, lack of parental engagement, and inadequate facilities. Funding mechanisms and tax structures often exacerbate the issue with some districts resorting to closing or consolidating schools, often laying the blame on every imaginable culprit, except the inadequacy of the public funding model, for the situation. If the school curriculum is dictated by state level politics, or if the local school board has uneven representation or divisive objectives of governance, what measures can local government take to support, advocate, and cultivate better educational opportunities and workforce development?

Cities have opportunities to cultivate a better climate for student outcomes. Providence, Rhode Island, recently received a $5,000,000 grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies for a pre-school program (here) to promote school readiness that uses proven technology to deliver coaching and tools to parents to close the word gap – low-income students hear 30 million fewer words before kindergarten than their peers from middle- and high-income families – and address major education issues before kids ever get to school.

Cities can also provide resources to schools to help lower high school drop out rates. At the University of Chicago, more than a decade ago, a team of researchers “…discovered that passing the ninth grade—earning at least five credits and no more than one semester “F” in a core class—is a better predictor that a student will graduate than are his or her previous test scores, family income, or race (The Atlantic published an article on this effort – available here). A student who passes ninth grade is almost four times more likely to graduate than one who doesn’t….” Using a series of interventions, schools have improved freshman pass rates. Among these interventions are areas where cities can cooperatively work with the schools. Public/private partnerships can step up with mentorship and tutoring opportunities within the community. Local government can cooperate with schools to monitor truancy. The results in Chicago have reduced high school dropout rates by double digits by moving from a sink-or-swim model to one “built on second chances.”

Charleston, South Carolina, has significant issues related to school inequality and a number of programs have emerged in recent years to develop strategies that can help. The Quality Education Project (you can visit their Facebook page here) brings together many community and academic leaders to strategize for ways that can improve the educational environment and student outcomes. Charleston Promise Neighborhood and Communities in Schools are involved in these efforts as well. The non-profit Meeting Street Schools worked closely with the school district in 2013 to launch a public school initiative at Brentwood that has seen remarkable results in only its first year (here). Some businesses have taken the initiative to launch student-run efforts that mimic real life conditions such as the student-run Heritage Trust Federal Credit Union at Goose Creek High School (here). The Lowcountry Maritime Society is using boat building to teach math and local history to students at Sanders Clyde and Burke (here).

Ultimately, everyone in a community has a stake in better schools, and the responsibility to ensure the success of these efforts requires a commitment on the part of parents, teachers, business leaders, workers, children, and retirees. Schools should have the resources, both financial and otherwise, for the next generation of graduates to make education a hallmark of our city’s success.

In 1988, the City Preservation Officer and Architect Charles Chase put a human face on the Board of Architectural Review. He recounted visiting a poor family in Cannonborough who was interested in making some minor repairs to the piazza of their Charleston single house. He had been concerned, at their initial meeting in his office, that the nature of the repairs were not replacing elements “in kind.” He began his visit by explaining this policy of replacing wood parts with identically made wood parts. He was invited inside the home where he found that much of the wood floor was missing, revealing the dirt below. He sighed empathetically, retracted his statements, and proceeded to approve the needed repairs.

In 1987, the Charleston Museum published a paper entitled “Between the Tracks: Charleston’s East Side During the Nineteenth Century,” funded by a grant from the City of Charleston, and a matching Historic Preservation grant from the US Department of the Interior, administered by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. The paper goes into great detail on the evolution of Charleston’s Neck (areas north of what is now Calhoun Street) and particularly the East Side’s 5th and 7th Wards. A digital copy of the book is available through the Lowcountry Digital Archive here.

The city of Charleston was incorporated in 1783 and its east/west limit on the peninsula was at Boundary Street (later known as Calhoun Street). The growing population south of this line subdivided lots and expanded into the centers of blocks with “courts” and lanes. Charleston’s merchants and craftsmen lined the waterfront and three streets – Broad, Tradd, and Elliott – where a largely pedestrian town was accommodated in close proximity to the waterfront. North of Boundary Street, known as the “Neck,” was slow to develop.

“The Neck had special advantages for city dwellers of African descent, especially for free Negroes and for slaves granted the privilege to work and live on their own. Rents were lower, real estate was more available and less expensive, and new houses could be built of wood, a practice discouraged within the city limits. The suburb also offered some respite from police surveillance and control; hence the Neck appealed to runaways, slaves “passing as free,” and other people eager to expand their personal liberty.”

Since much of this Neck was granted to “proprietor” families in the 17th century, their descendents with an eye to investment, began to develop the holdings into discrete communities, such as Harleston Village and Ansonborough. Further north and along the Cooper River, Henry Laurens assembled 99 acres and laid out the Village of Hampstead in 1763. It was deliberately modeled after 17th and 18th English suburbs with lots set around a spacious central square (now severed into quadrants by America and Columbus Streets). Notably, English-style alleys were avoided in an effort to discourage the clustering of slave residences on these ”hidden” roads. In spite of this gesture at its origins, several enterprising “free persons of color” invested in Hampstead lots, including Richard Dereef and his sister Susan Ann.

As one might find today, people in the 18th century determined where to live based on a number of factors: social, economic, and environmental. The Neck provided low rents, inexpensive lots, and the privilege of building wood houses (the threat of fire in the lower peninsula prompted regulations dictating the use of brick). Additionally, codes and laws that applied to the “free people of color” were relatively loose compared to those in other states, and many of these people from across the South made their way to Charleston for this relative freedom. Lots were subdivided to accommodate additional family members, friends, or just to provide income, using the heretofore forbidden “courts,” re-introduced between 1800 and 1850, to provide access to building on these “new” internal lots.

By the dawn of the Civil War, two-thirds of the city’s “free people of color” population lived in the 4 wards above Boundary Street. And by 1890, the houses of the Neck differed significantly in materials, with more than 90% constructed of wood, and size from the downtown houses. It is in this area where you find one-storey “freedman” cottages built for “free people of color” during the postwar period.

Just as historically was the case, economics, speculation, and investment remain at play in determining where people will live. African Americans remain a significant percentage of the population above Calhoun Street and in the neighborhoods extending northward to what is now known as the Upper Peninsula. The big difference now is that the trend includes the displacement of the remaining African American population. This shift will unfortunately undermine a key element of what makes Charleston culturally rich and diverse today. How to stem this evolution in an appropriate and embracing way will critically shape Charleston’s future and its livability.

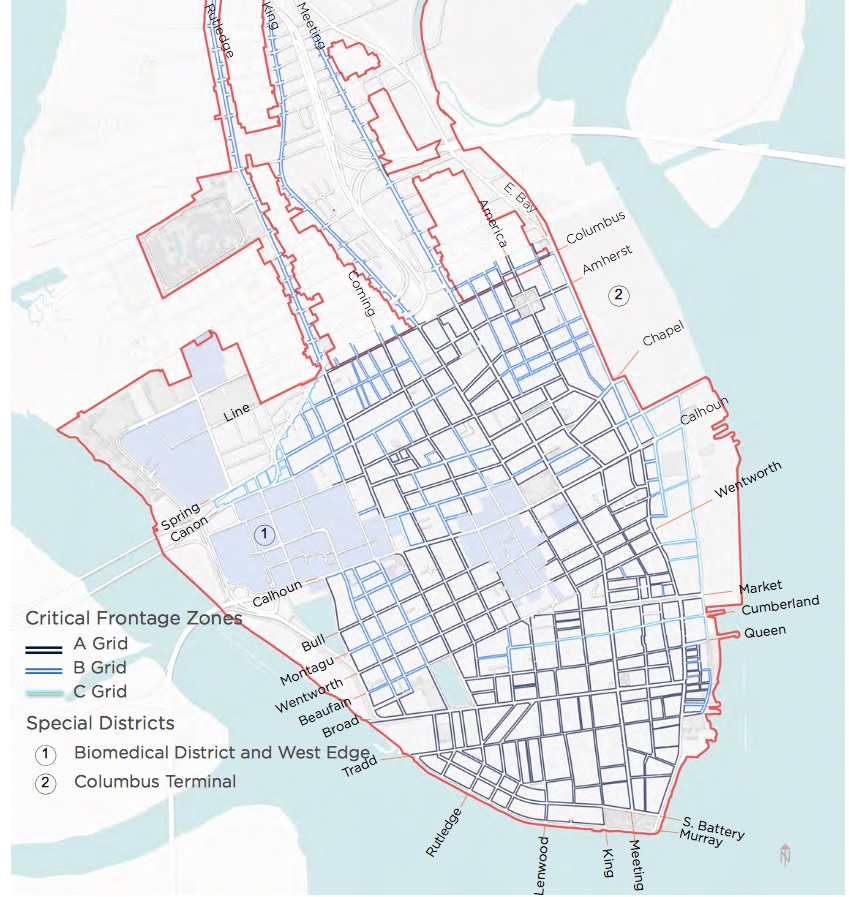

The proposed revisions to the Board of Architectural Review process (here) prepared by DPZ Partners have a few laudable recommendations. However, included in the proposal is a map illustrating “Critical Frontage” for buildings subject to the BAR review, showing properties along Rutledge, King, and Meeting among others, and extending well into the pre-dominantly African American neighborhoods north of Huger Street. The map suggests a kind of “gentrification strategy,” that perhaps should be reconsidered with input from the stakeholders within these communities (by all accounts, a population little represented in the meetings noted in the proposal to have occurred).

Aesthetics are the currency of power and whether we choose to discount the position of the disadvantaged is a choice that must be more carefully considered than a week’s worth of masterful salesmanship of the so-called “Charleston Brand” rendered to dramatic effect before a mostly privileged crowd.