In 1988, the City Preservation Officer and Architect Charles Chase put a human face on the Board of Architectural Review. He recounted visiting a poor family in Cannonborough who was interested in making some minor repairs to the piazza of their Charleston single house. He had been concerned, at their initial meeting in his office, that the nature of the repairs were not replacing elements “in kind.” He began his visit by explaining this policy of replacing wood parts with identically made wood parts. He was invited inside the home where he found that much of the wood floor was missing, revealing the dirt below. He sighed empathetically, retracted his statements, and proceeded to approve the needed repairs.

In 1987, the Charleston Museum published a paper entitled “Between the Tracks: Charleston’s East Side During the Nineteenth Century,” funded by a grant from the City of Charleston, and a matching Historic Preservation grant from the US Department of the Interior, administered by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. The paper goes into great detail on the evolution of Charleston’s Neck (areas north of what is now Calhoun Street) and particularly the East Side’s 5th and 7th Wards. A digital copy of the book is available through the Lowcountry Digital Archive here.

The city of Charleston was incorporated in 1783 and its east/west limit on the peninsula was at Boundary Street (later known as Calhoun Street). The growing population south of this line subdivided lots and expanded into the centers of blocks with “courts” and lanes. Charleston’s merchants and craftsmen lined the waterfront and three streets – Broad, Tradd, and Elliott – where a largely pedestrian town was accommodated in close proximity to the waterfront. North of Boundary Street, known as the “Neck,” was slow to develop.

“The Neck had special advantages for city dwellers of African descent, especially for free Negroes and for slaves granted the privilege to work and live on their own. Rents were lower, real estate was more available and less expensive, and new houses could be built of wood, a practice discouraged within the city limits. The suburb also offered some respite from police surveillance and control; hence the Neck appealed to runaways, slaves “passing as free,” and other people eager to expand their personal liberty.”

Since much of this Neck was granted to “proprietor” families in the 17th century, their descendents with an eye to investment, began to develop the holdings into discrete communities, such as Harleston Village and Ansonborough. Further north and along the Cooper River, Henry Laurens assembled 99 acres and laid out the Village of Hampstead in 1763. It was deliberately modeled after 17th and 18th English suburbs with lots set around a spacious central square (now severed into quadrants by America and Columbus Streets). Notably, English-style alleys were avoided in an effort to discourage the clustering of slave residences on these ”hidden” roads. In spite of this gesture at its origins, several enterprising “free persons of color” invested in Hampstead lots, including Richard Dereef and his sister Susan Ann.

As one might find today, people in the 18th century determined where to live based on a number of factors: social, economic, and environmental. The Neck provided low rents, inexpensive lots, and the privilege of building wood houses (the threat of fire in the lower peninsula prompted regulations dictating the use of brick). Additionally, codes and laws that applied to the “free people of color” were relatively loose compared to those in other states, and many of these people from across the South made their way to Charleston for this relative freedom. Lots were subdivided to accommodate additional family members, friends, or just to provide income, using the heretofore forbidden “courts,” re-introduced between 1800 and 1850, to provide access to building on these “new” internal lots.

By the dawn of the Civil War, two-thirds of the city’s “free people of color” population lived in the 4 wards above Boundary Street. And by 1890, the houses of the Neck differed significantly in materials, with more than 90% constructed of wood, and size from the downtown houses. It is in this area where you find one-storey “freedman” cottages built for “free people of color” during the postwar period.

Just as historically was the case, economics, speculation, and investment remain at play in determining where people will live. African Americans remain a significant percentage of the population above Calhoun Street and in the neighborhoods extending northward to what is now known as the Upper Peninsula. The big difference now is that the trend includes the displacement of the remaining African American population. This shift will unfortunately undermine a key element of what makes Charleston culturally rich and diverse today. How to stem this evolution in an appropriate and embracing way will critically shape Charleston’s future and its livability.

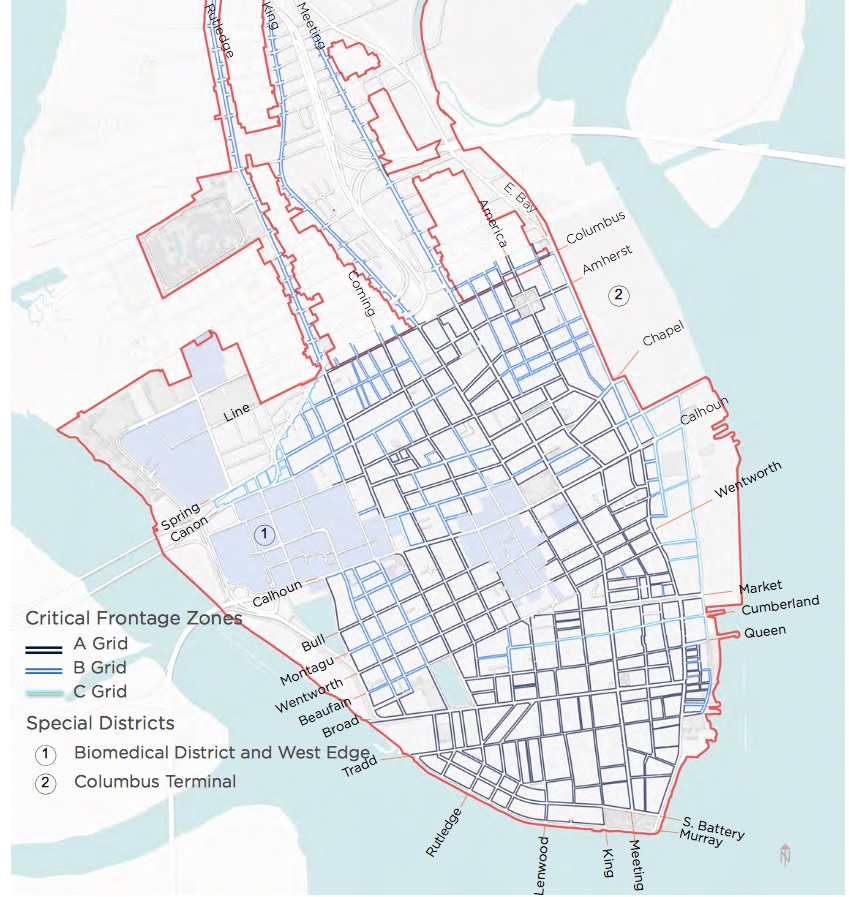

The proposed revisions to the Board of Architectural Review process (here) prepared by DPZ Partners have a few laudable recommendations. However, included in the proposal is a map illustrating “Critical Frontage” for buildings subject to the BAR review, showing properties along Rutledge, King, and Meeting among others, and extending well into the pre-dominantly African American neighborhoods north of Huger Street. The map suggests a kind of “gentrification strategy,” that perhaps should be reconsidered with input from the stakeholders within these communities (by all accounts, a population little represented in the meetings noted in the proposal to have occurred).

Aesthetics are the currency of power and whether we choose to discount the position of the disadvantaged is a choice that must be more carefully considered than a week’s worth of masterful salesmanship of the so-called “Charleston Brand” rendered to dramatic effect before a mostly privileged crowd.