That was the line printed at the bottom of the 1964 version of South Carolina’s Application for Registration to vote. The irony, of course, was that embedded within the application were tests or qualifications that particularly targeted the African American population and the poor for exclusion in the voting process. Here are two of the five “tests” of eligibility:

•I am not an idiot, or insane, a pauper supported at public expense or confined in any public prison.

•I will demonstrate to the Registration Board that: (a) I can both read and write a section of the Constitution of South Carolina; or (b) I own and have paid all taxes due last year on property in this State assessed at $300.00 or more.”

Or perhaps, you would prefer these questions from Georgia’s application for registration:

•Who is the Solicitor General of your State Judicial Circuit and who is the presiding judge?

•What does the Constitution of the United States provide regarding the suspension of the privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus?

•In what Federal Court District do you live?

•What are the names of the Federal District Judges of the state?

Now how about these examples of thirty questions on one of Louisiana’s literacy tests:

•Spell backwards, forwards.

•Print the word vote upside down, but in the correct order.

•Write right from the left to the right as you see it spelled here.

•Write every other word in this first line and print every third word in the same line, (original type smaller and first line ended at comma) but capitalize the fifth word that you write.

These examples and others may be found on the website of the Civil Rights Movement Veterans.

Some consider the elimination of these types of tests by virtue of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 merely a historical matter (Shelby County v. Holder). Others consider disenfranchisement of classes of voters to continue as a relevant question (see The Atlantic’s “What Does the Voting Rights Act Mean Today? or The NYTimes Magazine’s “A Dream Undone”). Racial issues remain a central theme in the political world of today – whether it is the gerrymandering the boundaries of a voting district, disqualifying US citizenship to naturalized children born in this country to immigrant parents, or requiring photo identification to cast a ballot.

Nine little Suffergets,

Finding boys to hate,

One kisses Willie Jones,

And then there are Eight.

The women’s suffrage movement has its own interesting history of opposition to the idea of women gaining the vote (see Mental Floss “The War on Suffrage“). The position of the privileged in both cases – race and gender – to deny the vote was often grounded in concerns with “societal disruptions.” The question of whether society would be better if blacks or women (or Hispanics or Asians) could vote, or whether it leads to a breakdown in peace and civility unfortunately remains a concern for some.

The recently released British movie, Suffragette, covers the UK’s movement (1918) and ends as the movement begins its inevitable shift to the United States (1920). The movie reveals the movement as bearing only a passing resemblance to the one embraced by mother and suffragette Winifred Banks of Mary Poppins fame. National Public Radio recently featured a story on the opposition to women’s suffrage in America (here). According to the political science professor Corrine McConnaughy, women who generally opposed the woman suffrage movement were women who were “doing, comparatively, quite well under the existing system, with incentives to hang onto a system that privileged them…Anti-suffrage leaders…were generally urban, often the daughters and-or wives of well-to-do men of business, banking or politics. They were also quite likely to be involved in philanthropic or ‘reform’ work that hewed to traditional gender norms.” This dichotomy can remain a difficulty for women who choose to work and even for those who seek political office. Attire, mannerisms, and “neglectful” child-rearing are often highlighted among peers, rather than qualifications, opinion, or expertise.

The overarching theme facing us at this point with voting is the question as to whether it is a “right” or a “privilege.” Given that “the right to vote” appears most often in the text of the U.S. Constitution – more than “freedom of speech,” “free exercise” of religion,” or the “right to keep and bear arms” – it would stand to reason that this point would not be an issue in the United States. But as we’ve seen already in the issue, for instance, surrounding the blacks’ right to vote, the exercise of voting is too often seen as something “granted by the powerful to the deserving.”

And, by extension, that privilege can be withheld if it is determined that YOU are less than deserving. Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, noted that Americans have been torn between “voting as a right and voting as something that only the right people should do,” even as we have ensured in our oversight of constitutional re-writes in Iraq or Germany that everyone is enfranchised regardless of race or gender (see The Atlantic “Voting: Right or Privilege?”).

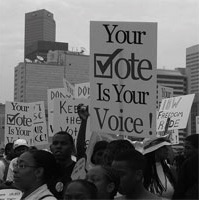

If we truly believe that voting is a “right” provided without question by the United States Constitution, then it is critical that we exercise that freedom to protect our democracy, to proclaim our dissent, and to demand a seat at the table of decision makers. An elected official represents everyone, not just those who voted them into office (or paid for them to get there).

With elections still in full swing this season – runoff elections are scheduled in Charleston for instance for November 17, 2015 – prepare to parse the truth from an onslaught of a slightly different variety as the remaining candidates:

•Try to attract voters who cast ballots for other candidates

•Try to cast opponents in questionable light, and

•Get the message out to the people who voted for them in the general election on November 3rd to remember and show up again to vote

So don’t let your vote slip away. Your voice is needed, your ideas are critical, and your participation can galvanize the unified and inclusive image Charleston has projected to the world.

Don’t let this historical moment become an illusion. VOTE on November 17.